The famous proverb is that “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life” which, amongst much else, suggests a certain rhythm to the nature of things. Its meaning, in the simplest sense is that real-world events are often inspired by creative works, intentionally or otherwise. Access to multitudes of archives and forums at a moment’s notice thanks to the internet has meant that this philosophy has, at times, crossed into the world of memes and conspiracy theories. How many times have the Simpsons predicted major world events?

Today, however, rather than art imitating life, I am far more interested in art depicting death. Specifically, the passing of England’s, and later the UK’s, monarchs. Now, art depicting death is by no means reserved for royalty, instead being something of a trend in the Victorian era even prior to the end of the Prince Consort’s life. Nevertheless, due to the hereditary nature of monarchy, these depictions carry a weight unto themselves. Summed up in one word, they represent succession. Whilst that might seem obvious, over the millennia this representation has been literal, symbolic, contemporary, and reflective.

Regardless of your own feelings about the British monarchy, you cannot have missed the news that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second passed away aged 96. In the days following, countless media outlets reported on the events as the ‘end of an era’, the dawn of a new period, and the death of the modern Elizabethan age. This article was originally sparked by the prompt ‘Best Art About Death’, which I posted in the first place. Despite the late Queen’s age, I was not expecting this news (the Queen Mother had lived to 101 and Duke of Edinburgh to 99), and I had chosen to write about The Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1833) by Paul Delaroche. The death of Elizabeth II made me think though. Why had the palace chosen that picture for her death announcement? What influenced other official social media pages, such as BBC News, Vogue, and Costa Coffee, to post the photographs that they did? Then, thinking back to the scene of Lady Jane Grey, which other British monarchs have had their deathbeds’ depicted and why?

For the late Queen and Duke of Edinburgh, simple photographs were released with others on social media choosing to mark the occasions by sharing their own artwork and collages. I do not recall seeing any scenes of their last moments, and if there were, they likely would not have been received as respectful gestures. The idea actually seems rather morbid but throughout history, this has not been the case.

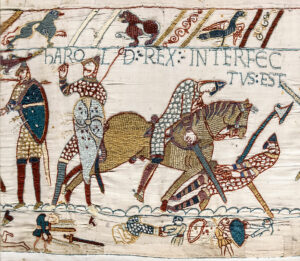

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered cloth from the 11th century, consists of 58 scenes across almost 70 meters. As with other medieval tapestries, it tells a story, starting with the death of Edward the Confessor, and the questions regarding his rightful heir and ending with the death of Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon King of the English. Arguably the most famous scene of the tapestry, Harold himself is difficult to identify. The traditional view is that he is the figure struck by an arrow in his eye however recent historians have disputed this, suggesting that he was, in fact, struck by a lance instead. Common medieval imagery reflecting the idea of King Harold as a traitor is embroidered throughout, thereby making William the Conqueror’s rightful claim to the English throne the ongoing thread throughout the tapestry. A story of succession in the literal sense; of how the Normans conquered England.

King Edward VI and the Pope

The monarch actually on his deathbed in this painting, Henry VIII, does not get name-checked in the title despite his place as one of Britain’s most famous monarchs today. The titular King Edward VI is the least famous of all five Tudor monarchs. Nonetheless, this c.1575 piece is believed to have been commissioned to commemorate the Edwardian religious settlement, as Elizabeth I successfully re-established the Church of England with her own brand of Anglicanism. Although that would seem to have the intention of acknowledging Elizabeth as the successor to her brother, both literally as monarch and religiously as head of the church, the scene itself is rather more on the nose with its depiction of the death of Henry VIII. He is literally pointing toward his longed-for son and heir who himself is surrounded by members of his council, including the soon-to-be Protector Somerset, Edward Seymour. Edward VI sat on the throne above the titular Pope who is quashed by ‘the worde of the Lord’ in English. A scene of how the Edwardian era was to succeed the reign of Henry VIII literally to the right with the regency council, and symbolically with the further suppression of the Roman Catholic faith within England. The depiction of these elements by the unknown Elizabethan artist undeniably suggests that the country would see this continued.

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche

Considering the title of this article and the painting itself, it is rather clear as to what the Execution of Lady Jane Grey depicts. It is what I had originally chosen to write about and what came to mind when I thought about the best art about death. Although not entirely historically accurate, this Paul Delaroche piece was completed in 1833, and captures the tragedy of events. A young girl, roughly 17 years old, blindfolded and led to the block, upon which she would meet her end. Her uncertain outstretched hand is the focal point of the painting, whilst the darkened background displays two grieving ladies-in-waiting, as one cannot bear to watch. In reality, the ‘Nine Days’ Queen’ was executed in the open air on Tower Green, but the indoor setting of the painting amplifies the drama of the story as Jane’s white clothes become more intensely juxtaposed, and their purity at this point in the events is more prominent. Unlike the Bayeux Tapestry and Edward VI and the Pope, the painting allows for the primary focus to remain on one event. Reflective upon the tragedy as a singular event rather than in relation to the monarchs before and after. In this way, it is very human, sympathetic, and personal in its depiction of Lady Jane Grey’s imminent death.

Queen Victoria On Her Deathbed by Sir Hubert von Herkomer

Recent, topical, news aside, Queen Victoria is the British monarch most associated with death. On the wave of nineteenth-century trends surrounding the afterlife, some of which she helped to popularise, the Queen was not known as the ‘Widow at Windsor’ for nothing. For almost 40 years she mourned the death of her beloved consort, Prince Albert, through, amongst other things, art depicting him in life and death. However, here it is the death of Victoria herself expressed through a simple watercolor painting. The whites of the tulle and flowers create a ghostly aura around the monarch. Nothing appears to be solid. The Queen is intangible, not as being a divine imperial being, but instead as a fragile and pale body lying on a bed of lilies. Bursting with their own symbolism, lilies most commonly represent purity, innocence and rebirth. It was the death of one era and the birth of another. From Victorian to Edwardian much could have been imagined of the future, literally in the painting as photographs and illustrations highlighted the line of succession and cultural iconography, however, this piece, as with the Execution of Lady Jane Grey, opted to linger on the moment. Drawing the mind to the passing of the Queen as an event singular as something to remember and reflect upon.

Art depicting death offers us a chance to reflect upon aspects of the individuals that have passed. Whatever your thoughts on the institution and monarchs personally, the death of a King or Queen is a historical event. The elements highlighted are fascinating and especially interesting to consider following the recent death of Elizabeth II. The examples I have discussed here are by no means the only ones although, given the historical significance of the deaths, it is a wonder why some have been depicted but not others. Certainly, there is room for more literal, symbolic, contemporary, and reflective pieces in keeping with the almost thousand-year tradition.