This Poe-inspired, English Gothic short film written and directed by Henry Fish is a vast improvement on his previous directorial efforts. I say that not intending to disparage any piece of Fish’s filmography, but it must be said that the increased budget of this project, as well as the smoke and mirrors created by the film’s stylistic elements, give A Serious House an air of professionalism that is absent both from the typical student film and some of the features of Fish’s that I have seen prior to this. Had I not known the director and the background of the production, I would never have assumed this was a student film. The film boasts a sophisticated quality – which has its roots in the silent horror classics – with a solidly stoic lead performance, which aids in showcasing the mind of the man behind the camera who is evidently fascinated with the horror genre in both the film medium and that of literature; knowing that the director is a former student of literature it is not hard to see where he gets his inspiration from.

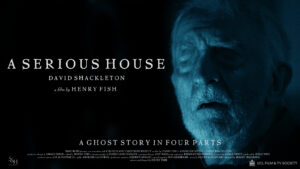

In a similar vein to Limelight, (another horror short Fish previously co-directed with the script supervisor for this film, Khairah Boukhatem), A Serious House has only one character present throughout the entirety of the film; a lonely, guilt-ridden Priest played by David Shackleton – a professional actor with credits ranging from an adaptation of Jonas Jonasson’s The 100 Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared, and 2018’s Holmes & Watson. And like Limelight, A Serious House has its horror elements founded upon a universal fear – one recently experienced by anyone who will come around to watching this film – as the director once again taps into our own life experiences; the central horror of A Serious House is isolation.

The plot of the film is strangely straightforward on a surface level for a horror short. The film follows a nameless Priest lamenting the loss of his congregation after an unnatural plague has claimed the life of every man, woman, and child; everyone, but this mysterious Priest whom we first see praying, on his knees, informing his God of the loss of his whole community (before burying one final body). This plague did not appear to discriminate; killing everyone but the Priest; this will undoubtedly resurface a few memories within the viewer’s mind. Memories of a time when we all shared the same uncertain fate of a potential death, at the hands of a plague that came with no warning. The role the Priest has is his proverbial cross to bear in this nightmare scenario. A priest knows everyone in his community; therefore, he knows everyone who dies. We, during the COVID-19 pandemic, had a luxury that God did not afford to the Priest: we did not know everyone who died in the pandemic, but the local priest of a medieval village certainly would have. The audience is well aware from the Priest’s prayer that he no longer has a congregation, but it still sends a shiver down your spine when the camera cuts to all those empty pews.

Everyone can relate to the Priest, which is the strong point of this film; the lead performance does not need to be a powerhouse exhibition of acting for the audience to empathise with his position; we may have also been in a similar situation when the most terrifying thing imaginable is an unexpected knock at the door when you are all alone. In a sense, the nucleus of the short is Hitchcock’s classic adage of nothing being more terrifying than a locked door. While we never truly see who or what was knocking on the door in the night, the atmosphere of horror is perfectly conveyed by the director’s stylistic choices and the homages made to horror classics through Sebastiano O’Grady’s cinematography.

The claustrophobic aspect ratio – channelling Robert Eggers’s The Lighthouse – perfectly conveys the loneliness of the Priest, even though when Shackleton takes the centre of the frame, there is still nothing but a vast emptiness on either side of him. The film is a veritable love letter to Gothic horror since the establishing shots of St. Mary’s Church (where the on-location shooting took place) are reminiscent of Nosferatu’s castle in the Carpathians, from F. W. Murnau’s 1922 vampire classic; while the shots of the moon during the night would not have been out of place in George Wagner’s The Wolf Man.

Though by far my favourite aspect of the film – which clearly unveils my predilection for the silent horror classics – is the choice to tint sections of the film (with yellow signifying day and blue inversely representing night) as opposed to just having the film in black and white; it may be a little too on the nose for some cinephiles but personally, as a fan of the genre it was very much an appreciated touch.

However, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the one negative aspect of the film, which is the sound. While for the majority of the film the sound effects consist of a constant howling wind that verges on screams, said sound is iffy in the first two parts. This is due to the nature of the location shooting – it is rather hard to tell whether what you are hearing is either a deliberate choice or just a nearby motorway. It does slightly fracture the verisimilitude of the whole affair, but it is a very small gripe to have with a short film – which again, is a testament to its overall quality.

Ultimately, the beauty of this film is skin-deep by virtue of the ambiguous nature of its narrative. Since the film will undoubtedly conjure up memories of our individual experiences of loss, loneliness, and quarantine, your interpretation of the film (specifically its ending) will, like my own interpretation, derive from how you responded to living in isolation during the numerous lockdowns of the pandemic.

For me, it feels as though Fish has taken one of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous tales in ‘The Masque of the Red Death,’ and poses the question of what if Prospero was not a Prince cowering in a castle, hosting an endless party for rich nobles, while a plague rips through his village below, but instead a lonely and humble Priest living in an earthly purgatory in a now abandoned church after he has essentially lost his whole world after everyone he knows has died. This for me is the spine of the film, but the ending is the pivotal informing scene where your verdict of the film as a whole will emanate from. The second I saw the ghost, I immediately noticed the make-up that was on display; Shackleton wears a clown white face, with potentially red lips, and pitch-black slanted eyebrows; in the film’s final moments, the ghost has the face of the Mephistopheles of Goethe’s tragic play Faust. My familiarity with Fish’s work leads me to the conclusion that to have the ghost bear the classic make-up of the Mephistopheles is not a coincidence; which presented my cynically inclined brain with so many questions. Why is the Priest the only one who was spared death? Is the Priest seeing a future echo of himself, which is why the ghost appears as his doppelgänger? Is he responsible for the plague? Does he enjoy the isolation that the plague has granted him?

The film is something that definitely sticks with you after watching it. The more I thought of it, my mind was cast back to the Burgess Meredith-led episode of the Twilight Zone called ‘Time Enough at Last.’ Meredith plays an ordinary man living in contemporary 60s America who after surviving a nuclear attack is seemingly the only survivor; in a nuclear wasteland he finds an ersatz paradise where he can finally be alone, away from pestering people; in isolation he finds solace. To me, this is what I feel has happened to the solitary Priest. Perhaps the Priest’s terror of hearing a knock at the door stems from the fact that he is no longer alone. A bitter truth that few are brave enough to admit is that some people do enjoy isolation, just as some of us enjoyed quarantine. The significance of the make-up tells me the Priest struck a Faustian bargain with some sinister entity that would grant him the desired isolation from his petulant congregation. Alas, it would come at the cost of the deaths of everyone in his village, and eventually his own, in a twisted monkey’s paw-esque scenario. To me, the very beginning of the film shows a guilt-ridden man confessing to his God what he has done.

Fish’s A Serious House is a meticulous Rorschach of a horror movie, chock full of references to films and literature, not to mention plenty of supernatural elements for the viewer to consider, since the night after the central visitation the Priest is not dead but rather he is entirely absentas vibrant colour (potentially indicative of life) returns to the village. A Serious House is a film you certainly will not forget regardless of how many times you watch it. Its true horrifying aspect is how it never leaves you since there is so much to think about it. Though worst of all, you may realise something about yourself and your experiences after watching it. The Priest is a partial reflection of ourselves during a moment in time we all experienced. How you experience isolation will dictate how you see the Priest. My interpretation tells me everything. What does yours tell you?

‘A Serious House’ by Henry Fish is available on YouTube, Vimeo, Twitter, and Instagram. Watch the trailer below…